Analytic philosophers try to understand what it means to exist.

The never-catastrophe death of analytic philosophy

The death of analytic philosophy has been announced many times. Talk of 'postanalytic philosophy' has started upwardly, then fizzled out again, repeatedly for more than than three decades. And however analytic philosophy somehow seems to go on to be with us equally the dominant force in academic philosophy.

It might exist thought that analytic philosophers take experienced a salubrious (and mild) identity crisis. They have come to see that they have much in common with other approaches, so are less inclined to insist on their ain identity. On the other mitt, so the thought continues, in that location is still a distinctive way in philosophy that can be aptly chosen 'analytic' (characterized, perhaps, past clarity of argumentation in its cocky-presentation and by openness to vigorous, non-hierarchical debate).

Or perhaps the point is that there are different ways of conceiving of 'analytic philosophy'—there is, after all, considerable disagreement about what analytic philosophy is. If that'south then, and so possibly information technology is live in one of these senses, but not in others. Perhaps in the past analytic philosophy thought of itself as a noun programme, but the viability of such a programme came to seem questionable. And and so what we are left with is a more pocket-sized kind of analytic philosophy — a modesty mayhap reflected in a less strident opposition to alternative approaches to philosophy among analytic philosophers today.

Analytic philosophy may seem more diffident today, and more sensitive to the other. It is true that a recent growth of historical self-awareness within analytic philosophy, and the growth of the history of analytic philosophy as a subdiscipline, have helped make it more than cocky-questioning. This development reflects a remarkable overcoming of analytic philosophy's previously staunchly ahistorical cocky-formulation, which had tended to keep its past buried and subconscious from view. Nevertheless analytic philosophy is by no means unpleasing or on the style out, but is an undeniable, and ascendant, part of the social reality of academic philosophy. Despite seemingly being endlessly in its expiry throes, it appears as alive as e'er. I will at present endeavour to tell the story that explains how this can be.

The birth of analytic philosophy is ofttimes thought to exist located in a defection by Bertrand Russell and G. East. Moore against the British Idealism into which they had been educated at Cambridge. Such a defection undoubtedly took identify, even if the break with Idealism was not quite as clean as the traditional myth imagines. Only the truth is that what we know as 'analytic philosophy' was not set in motion by Russell and Moore, or before by Gottlob Frege, or by anyone else. It is, instead, a post-1945 construct in which a diverseness of disparate before approaches were welded together in a deliberate act of creation.

If there is a decisive moment of birth, it is the publication in 1949 of Readings in Philosophical Analysis, whose editors, Herbert Feigl and Wilfrid Sellars, consciously set out to shape the teaching of philosophy in the Us in an 'analytic' mould. This publication, and others such as Arthur Pap's Elements of Analytic Philosophy (also published in 1949), helped crystallize the thought of 'analytic philosophy', in which a number of dissimilar approaches to philosophy were combined: the 'logico-analytical method' of Russell, the commonsense/realist 'analysis' of Moore, the logical positivism of the Vienna Circle, the logic of the Lwów-Warsaw school, and American approaches flowing from the pragmatist and realist traditions. Past 1958 a group of curious French philosophers could invite leading Anglophone philosophers to a conference at Royaumont under the title La philosophie analytique, to come across what all the fuss was about. In the very same period, however, the death knell was already existence sounded for analytic philosophy in various quarters. In 1956 the Oxford philosopher J. O. Urmson published a history of analytic philosophy, Philosophical Assay, which ends in an obituary for what he calls 'the old analysis'. The obituary notices take kept coming. In his book Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979), the apogee of a sustained self-critique of analytic philosophy that had begun with the publication of West. 5. Quine's 'Ii Dogmas of Empiricism' in 1951, Richard Rorty wrote: 'I do not think that in that location any longer exists anything identifiable as "analytic philosophy", except in some […] stylistic or sociological way'. In the wake of Rorty's pronouncement there was much talk of 'postanalytic philosophy' (run into in detail John Rajchman and Cornel Due west (eds.), Postanalytic Philosophy, 1985). Since then we have never quite stopped hearing about 'postanalytic philosophy', although no such affair has ever decisively taken over from analytic philosophy.

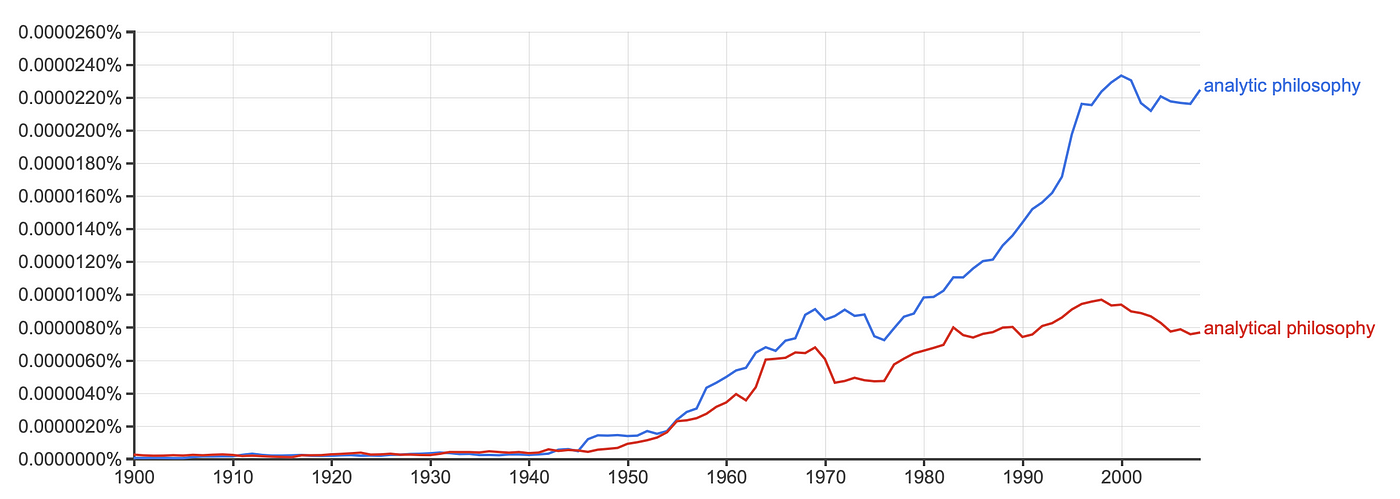

The merits that analytic philosophy was born afterwards 1945 will seem startling to many. Wasn't at that place widespread talk of 'analytic philosophy' (or 'analytical philosophy') before that? The answer is no, at least if what is said in print is our guide. This by itself doesn't settle whether analytic philosophy existed—mayhap information technology wasn't necessary to utilise the phrase. Only information technology is hitting that philosophers felt the need to self-use the characterization only after 1945. This Google Ngram (showing the incidence of the phrases 'analytic philosophy' and 'analytical philosophy' in books published over the period 1900–2010) illustrates the bespeak well:

The term 'analysis' was, certainly, much used by both Russell and Moore (fifty-fifty if they meant different things by it), and the founding of the journal Analysis in 1933 was a pregnant upshot (not least since the question of how to practise philosophical 'analysis' was much discussed in its pages). But the phrase 'analytic philosophy' is in no style commonplace until after 1945. In the first appearances in impress of the phrase 'analytic philosophy', the authors use it to express a disquisitional mental attitude to the approaches they run into as falling under it (R. G. Collingwood in An Essay on Philosophical Method and W. P. Montague in 'Philosophy as Vision', both published in 1933) — although John Wisdom had written with approval of 'analytic philosophers' (in a volume on Jeremy Bentham) in 1931. In that location seems to be nothing before than this, other than a lone use of 'the analytical philosophy' in an anonymously authored report of a meeting of the Aristotelian Gild in 1915, where the phrase appears in a description of a point fabricated by Russell in the discussion session. (The recent paper by Andreas Vrahimis from which I know this, past the way, documents a fascinating episode in the demonization of the French philosopher Henri Bergson tirelessly prosecuted past Russell, through the story of Russell's interaction with the little-known philosopher, psychoanalyst and defender of Bergson, Karin Costelloe-Stephen.)

The idea that there was i thing that philosophers were doing prior to 1945 that could exist called 'analytic philosophy' is, and so, a retrospective estimation. In this interpretation, a number of different approaches were welded together, equally per Feigl and Sellars's conception. The separate strands had earlier been nicely laid out in a two-part paper past Ernest Nagel, published in The Journal of Philosophy in 1936, and entitled 'Impressions and Appraisals of Analytic Philosophy in Europe'. (This is patently the first publication with 'analytic philosophy' in its title.) Nagel had been trained in the United States, and the articles are effectively a travel diary of a twelvemonth in which he tried to run into representatives of various kinds of what he identified every bit 'analytic philosophy' in Europe (including Britain). Nagel's four big categories (mapping pretty closely onto those of Feigl and Sellars, except for their specifically American category) are: Moorean analysis as practised in Cambridge; logical positivism; the work of Wittgenstein; and Polish logic. Although Nagel sees these approaches every bit sharing a common spirit that is aptly designated as 'analytic philosophy', he also draws attention to the conflicts and disagreements betwixt them. For the logical positivists, the point was to bow downward before the natural sciences and restrict oneself to the analysis of empirical statements. Others thought that the work of analysis was more substantive than this: there was independent philosophical understanding to exist gained through information technology, not merely the clearing up of whatsoever mess that the empirical sciences might leave. What Nagel further draws our attention to is that the approaches he groups together were not e'er friendly to each other. Logical positivism, for example, was by no means well-received amongst the majority of British philosophers. (As Michael Dummett later on wrote, when he was educatee in Oxford 'the enemy was Carnap', a key figure in the Vienna Circumvolve, not Heidegger.)

Reconstructing this story non only helps to dispel the idea that there was ever a unified kind of philosophy called analytic philosophy, and to show that instead 'analytic philosophy' is an amalgam created after World War 2. It also displaces a standard narrative well-nigh analytic philosophy, in which its founding act is the then-chosen 'linguistic turn', through which the problem of significant was made central to philosophy. This story is told in its near ambitious versions by Michael Dummett and by Ernst Tugendhat, both of whom have taken the idea of a substantive programme of 'analytic philosophy' very seriously. Dummett finds the 'first clear case' of the linguistic turn to be Frege'due south Foundations of Arithmetic of 1884.

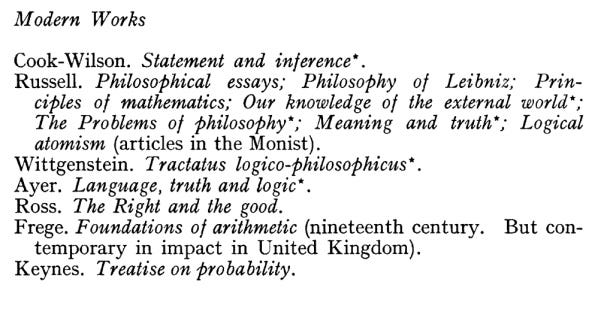

It is true enough that from the 1950s onwards Frege was a major fixture. Merely this was largely a new development; simply now did report of Frege get mainstream, with Foundations of Arithmetic existence published in English translation for the first fourth dimension in 1950. In a UNESCO report entitled The Teaching of Philosophy of 1953, Foundations of Arithmetics is included in a listing of typical readings for a British philosophy undergraduate, with the specification 'contemporary in touch on in the Great britain'.

As Greg Frost-Arnold has persuasively argued, the question of pregnant wasn't actually key to the catechism of analytic philosophy before World War Two. A notable exception, Frost-Arnold points out, is Susanne K. Langer — a philosopher, incidentally, with ties to 'continental' schools of idea through her involvement in Ernst Cassirer. Presently plenty, however, significant would occupy a central place in analytic philosophy, especially in the so-called 'Davidsonic boom' inspired by the attempts of Donald Davidson to provide a 'theory of pregnant' for natural languages on the model of the logician Alfred Tarski's truth-theory for formal languages. This period instructively shows upward tensions in what analytic philosophy had become. Wittgenstein, for 1, had poured cold water on the thought of explaining meaning, and even so this is what the Davidson-inspired theories seemed to be in the business of doing (a productive tension that can be seen animating some of the most artistic work in analytic philosophy in this period).

Then things took a dissimilar turn. Analytic philosophy now entered a phase marked past a new methodological insouciance. Metaphysics was fine again, every bit was political philosophy (an area driven almost entirely by a single book, John Rawls'south A Theory of Justice, published in 1971). To many it now didn't seem to affair anymore whether there was a programme of analytic philosophy or non: it was evident plenty that there was work to get on with. The methodological self-awareness that had seemed so refreshing in the 1950s had gone, giving way to a sense of easy familiarity with established protocols and procedures. Past dissimilarity with the searching work of G. E. Thousand. Anscombe in the 50s to understand the nature of man action 'for the sake' of practical philosophy, for example, there now adult 'action theory' no longer specially concerned about its raison d'être. And much metaphysics seemed to recall of itself as like physics, but deeper.

From here on, Rorty'south diagnosis seems borne out: analytic philosophy now existed only 'in some stylistic or sociological way'. It was a set of well-recognized procedures without much need to explain to itself why it was post-obit these procedures. To say that analytic philosophy was now a stylistic or sociological phenomenon may make it seem like information technology had been effectively defanged and rendered harmless. Lacking distinctive doctrines or aims, it was no longer actually in contest with other approaches: it was really just careful, clever thinking. But this is very far from the case. That the analytic philosophy we have ended up with exists as a 'sociological' phenomenon is a very important fact about where bookish philosophy has been since, and still is today.

Analytic philosophy was one time (in the 1950s) a strident, crusading movement. Having been constituted by Feigl and Sellars, and others, it speedily gained control of American philosophy departments. Information technology was particularly well-placed in this regard in the menses of McCarthyism, thanks to its apolitical credentials. While some analytic philosophers were on the left, and both Wittgenstein and J. L. Austin travelled to the Soviet Matrimony, their philosophical work remained untainted by politics (with the exception of the lone Marxist logical positivist, Otto Neurath).

An object lesson in the trend of analytic philosophy to mark itself out as distinctive from the rest of philosophy is the divide that information technology created between itself and what it chosen 'continental philosophy'. The distinction (a commonplace which anyone who has participated in academic philosophy is familiar with) is sometimes criticized as somehow mistaken or silly. After all, Frege, Schlick, Carnap, Wittgenstein, Waismann, Feigl, et al., were obviously from continental Europe. And, every bit Bernard Williams pointed out in a lecture given at the opening of a Centre for Mail service-Analytic Philosophy (long since defunct) at Southampton University in 1997, it seems oddly misplaced—as he put it, a bit like 'classifying cars equally Japanese and front-bike drive'. Certain enough, 'analytic' is a methodological term, whereas 'continental' is a geographical one, and so Williams rightly indicts the distinction every bit what Gilbert Ryle chosen a 'category error'. Crucially, however, it is analytic philosophers who are the originators of the label 'continental philosophy', to designate an out-grouping to their in-group. In doing and so, they treated a broad assortment of disparate approaches as if they belonged together—phenomenology, existentialism, hermeneutics, deconstruction, besides every bit forms of 'theory' that think of themselves as anti- or mail-philosophical. This made sense from the bespeak of view of analytic philosophy: continental philosophy was what could, by its lights, exist safely ignored. No one always called themselves a 'continental philosopher', until this characterization had stuck in places where analytic philosophy possessed academic hegemony, such as the U.s. and Great britain. Just as a result of analytic philosophy's act of cosmos of continental philosophy, there has since then really been such a matter every bit continental philosophy (reflected in MA programmes in continental philosophy, societies for continental philosophy, and so on). Social reality is reality, too.

Analytic philosophers may speak in conciliatory tones about healing the rift with continental philosophy (a rift, to be sure, of their own making). Only in order for this to happen finer, analytic philosophy must regain methodological self-awareness. In today'due south globe, analytic philosophy faces a range of new challenges. It has heard the phone call of feminism, of disquisitional race theory, and of the movement to decolonize the curriculum, and it is actively in the business of trying to mind these calls. Academic philosophy faces a particularly acute inclusivity problem, fifty-fifty past the standards of the academy: representation of women and of non-whites in the profession is shockingly poor.

Any its enthusiasm to exercise so, yet, in that location are specific reasons why analytic philosophy is peculiarly underequipped to meet these challenges. Although it places accent on open and non-hierarchical debate, information technology conceives of such contend inside a problematic framework. In line with the apolitical profile information technology gave itself in the years following World State of war II, analytic philosophy tends to conceive fence on the liberal model of a 'marketplace of ideas'. This is unsurprising, since the 'apolitical' are, just past virtue of sealing themselves off from political engagement, particularly susceptible to unwittingly falling into line with the prevailing ideology and its structures. The problem with the marketplace of ideas, as with the commercial market place of classical and neoclassical economics on which it is modelled, is that it treats each participant in the marketplace as de facto engaging in exchange on equal terms. Just as in the neoclassical commercial marketplace holding qualifications are irrelevant (the propertied and the non-propertied enter 'on equal terms' in the sense that their holding buying is irrelevant), in the liberal marketplace of ideas everyone is but causeless to enter on equal terms. If the points of feminists and disquisitional race theorists that analytic philosophers are seeking to have on board are right, however, this whole conception of equal engagement stands in need of critique. And the very ideas of feminism and disquisitional race theory are deprived of their very signal and rendered impotent if discussion takes place on these terms.

There is bully promise in the prospect that analytic philosophy might develop and grow by taking on these challenges. But it must overcome the illusion that it is already equipped to do and then. Analytic philosophy is non innocent. In that location is a dangerous childlikeness in its insistence that anyone can come up and fence, and everything volition be considered from scratch, treating anybody as equals. It volition abound out of this only through active appointment with approaches that it claims no longer to despise, including the piece of work of other humanities disciplines. It volition non exist enough to regiment some of the ideas in, say, disquisitional race theory, extracted from some other literature using its own procedures and on its own terms, into its ain format. Information technology will need to open itself to immersion in cultural, social and political reality. It will and then accept the prospect of beingness, for the commencement time, truly alive.

Source: https://christophschuringa.medium.com/the-never-ending-death-of-analytic-philosophy-1507c4207f93

0 Response to "Analytic philosophers try to understand what it means to exist."

Post a Comment